Altering Genetic Destiny: The Life-Saving Power of Lynch Syndrome Detection

By Natalie Larsen

“If you could do something that would prevent you from getting cancer—that could detect it early—wouldn’t you want to know that?”

Cancer. The word alone is often enough to make one’s heart drop into their stomach, considering it is not typically a word that is followed by any kind of good news. Much of that heart-dropping fear we have come to associate with cancer also stems from a deeper-rooted fear of the multitude of unknowns that go hand-in-hand with cancer: What stage is it? Has it, or will it, spread? Is it treatable?

The good news is that every single day, researchers are making great strides to catch the runaway train that, in earlier days, once was a cancer diagnosis. Every single day, science and technology are advancing to better detect, diagnose and treat the various forms and stages of cancer. Every single day, health advocates and science communicators are finding ways to amplify valuable information and spread awareness to broader audiences, so that people in those audiences are better able to advocate for themselves and their loved ones in the doctor’s office.

Knowledge is truly power and the best weapon we can wield when it comes to safeguarding our health, which is what brings us to a common, but not well-known condition called Lynch syndrome and its relationship to cancer.

All in the Family Genetics

If you were to try and boil it down to a single cause, you could say cancer is caused by gene mutations in cellular DNA, which lead to rapid, uncontrolled development and division of abnormal cells. These gene mutations can occur for a number of reasons, including environmental and occupational risk factors such as exposure to UV radiation or carcinogens and lifestyle factors such as smoking, but a number of cancers are attributable to biological factors such as hereditary genetic mutations passed on to us by our parents.

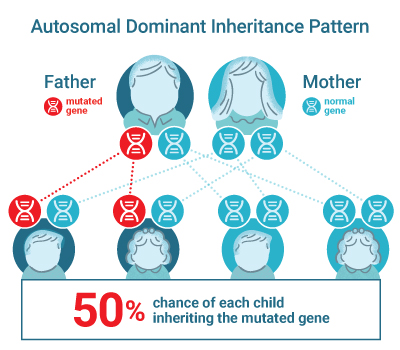

In some families, cancer occurs more often than expected. For example, a family history of colon or endometrial cancer specifically, is usually a good indicator that a genetic factor is at play. There are two genetic syndromes most commonly associated with colorectal cancer: Familial Adenomatous Polyposis and Lynch syndrome. These syndromes each demonstrate an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern, meaning that if one parent has the gene mutation, there’s a 50% chance that the mutation will be passed on to each child and only one inherited copy of the altered gene in a cell is enough to increase cancer risk. This genetic risk is consistent regardless of gender of the parent and the child.

Familial Adenomatous Polyposis (FAP) results from autosomal dominant mutations in the tumor suppressor gene called APC, and accounts for approximately 1% of all colon cancers. Most people with FAP develop multiple colon polyps by the age of 39 and, if not detected and treated, these polyps will almost always develop into cancer. Typically, FAP is diagnosed when your doctor finds a large number (>100) of colorectal polyps, and blood tests can be used to confirm the presence of mutations associated with FAP.

Lynch syndrome, historically known as hereditary nonpolyposis colon cancer, is the most common form of hereditary colon cancer and can be attributed to roughly 3% of all colon cancers, or 1 in every 33 colon cancer patients (1). Lynch syndrome is caused by autosomal dominant mutations to the major mismatch repair genes MLH1, MSH2, MSH6 or PMS2 as well as the EPCAM gene that inactivates MSH2. In addition to colorectal cancer, people with Lynch syndrome have an increased risk of developing certain other cancers, including endometrial, ovarian and stomach cancer.

Symptoms of a Silent Killer

Lynch syndrome tends to fly under the radar in both the general public and the medical community because there aren’t specific symptoms that can be used to identify it. One of the only early indicators is a colon or endometrial cancer diagnosis that occurs at an atypically young age. For patients and doctors who don’t know about Lynch syndrome, however, the underlying genetic cause and associated risk can still be overlooked, as it was for Jacqueline Rush, who lost her battle with colorectal cancer at the young age of 23.

Jacqueline first began experiencing symptoms in high school, but due to her doctor’s lack of Lynch syndrome awareness and the widely-held belief that you couldn’t get colorectal cancer at such a young age, her cancer wasn’t diagnosed until she was 20 years old. It wasn’t until she was undergoing treatment that it was discovered that the underlying cause of her cancer was Lynch syndrome, a discovery that, along with earlier and proper cancer screening, would most likely have saved her life. Joan Rush, Jacqueline’s mother and co-founder of the Jacqueline Rush Foundation, teamed up with Heather Tomlinson, PhD, Former Director of Clinical Diagnostics at Promega on an episode of Access Health on Lifetime, to share Jacqueline’s story and spread awareness about Lynch syndrome.

Lynch Syndrome Screening Solutions

To determine the likelihood of Lynch syndrome, there are simple screening tests that can be performed on the tumor tissue of patients diagnosed with colon or endometrial cancer. The two most common screening tests are immunohistochemistry testing (IHC) and microsatellite instability testing (MSI). The results of these tests can be used to determine if more specific genetic testing should be considered.

Immunohistochemistry is a screening test for Lynch syndrome tumors that looks for the proteins expressed by the mismatch repair (MMR) genes. If the MMR genes are functioning properly, the proteins will be present. The absence of a mismatch repair protein increases the likelihood that the patient has Lynch syndrome and indicates that further genetic testing should be performed.

High microsatellite instability (MSI-H) in tumor tissue has come to be known as a trademark biomarker of Lynch syndrome. MSI-H status indicates that certain sections of DNA called microsatellites have become unstable and changed in length due to the major MMR genes that correct errors during DNA replication not functioning properly; the spell check is essentially missing on the DNA. A DNA analysis test is used to determine MSI status. The test is performed on both normal and tumor tissue. If the results for the tumor differ from the normal tissue results, the tumor is considered MSI-H. It’s important to note that not all tumors that are MSI-High are associated with Lynch syndrome, which is why further testing is needed for patients with MSI-H tumors.

Following confirmation that a patient is either missing one of the MMR proteins or is MSI-high, the next step is to test the MLH1 promoter for methylation, which is a common cause of MMR deficiency. If no methylation is detected, then the final step in the testing cascade is germline sequencing of the four MMR genes in order to determine whether the patient has a Lynch syndrome-associated mutation or if the MMR deficiency can be attributed to double somatic mutations. Around 4% of patients who complete this testing cascade will learn that they are positive for Lynch syndrome, meaning they inherited a MMR gene mutation from a parent. Following this diagnosis, genetic counselors will work with patients to help explain the significance of Lynch syndrome status and walk through next steps with them 2.

Know Your Colorectal Cancer Risk

According to the International Agency for Research on Cancer at WHO, the global burden of cancer is immense, with an estimated 18 million new cases diagnosed and 9.5 million people who will lose their battle with cancer annually. Globally, colorectal cancer is the third most common type of cancer, and it is the second most common cause of cancer-related death, with an estimated loss of 880,000 people to colorectal cancer each year.

Despite its high incidence, colorectal cancer is unique in that it is one of the most preventable and, if detected early, most treatable forms of cancer, which is why it is so important to know your personal and family medical history. If you have a family history of an immediate family member (like a parent or sibling) or have multiple family members with colorectal cancer or polyps, you are likely at increased risk for developing cancer as well.

Lynch Syndrome cancer statistics from Cancer.Net accessed August 28, 2020.

General public cancer statistics from the American Cancer Society accessed August 28, 2020.

It is estimated that 1 in every 279 individuals have Lynch syndrome, but roughly 95% of them are completely unaware that they have it 3. If you have had a colorectal cancer diagnosis or a high incidence of cancer in your family, it is a good idea to talk to your healthcare provider about whether genetic testing and counseling are right for you.

Genetic Counselors work with patients and their families to review their medical history, including their Lynch syndrome status. They serve as both dedicated guides and interpreters of the complicated language of genetic testing and tumor screening results, explaining what those results mean for the individuals and their families while also illuminating a path forward, regardless of the test outcome 4.

Knowledge is Power

If you discover you are Lynch-positive, you and your healthcare professional will be able to make better, more informed decisions regarding your health before the onset of cancer. You can take steps to mitigate your risk through earlier and more frequent screenings for pre-cancer or early-stage cancer, or through preventative surgeries. Knowing your Lynch status can also arm your family members with useful information that could be potentially life-saving, including knowing which mutation(s) they should be tested for.

Though a positive result for Lynch syndrome could make you feel the opposite of positive, seeking out that information is actually an empowering thing. Knowing your personal history, your Lynch status, and your risk, puts the ball back in your court and ultimately gives you the power to mitigate your genetic fate.

“…Knowing you have Lynch syndrome is really important and the benefits of knowing, is that it’s life-saving, it’s powerful and it gives you the power to change your genetic destiny, instead of leaving it up to fate.”

References

- Moreira, L. et al. (2012) Identification of Lynch syndrome among patients with colorectal cancer. JAMA. 308(15): 1555–65.

- Villanueva, J. (2018) Dreaming of Universal Tumor Screening. Promega Corporation

- Win, A. K. et al. (2017) Prevalence and Penetrance of Major Genes and Polygenes for Colorectal Cancer. Cancer Epidemiol. Prev. 26, 404–12.

- Syngal, S. et al. (2015) ACG Clinical Guideline: Genetic Testing and Management of Hereditary Gastrointestinal Cancer Syndromes. Am. J. Gastroenterol. 110(2): 223–263.